With Brexit trade talks finally starting this month, relations between London and Brussels could hardly be more strained. French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian went so far as to say, “I think on trade issues and the mechanism for future relations, which we are going to start on, we are going to rip each other apart.” Anadolu Agency asked four Brexit experts to weigh in on what lies ahead.

Divergence

Britain wants the right to set its own rules, zero-tariff trade on manufactured and agricultural goods, fisheries to be decided in a separate annually-renewed agreement and equivalence on financial services. “Diverging from EU rules would send a strong message that the U.K. is now ‘free’,” said Chris Stafford, a PhD candidate at the University of Nottingham’s Politics and International Relations Department. “The U.K. government can only survive if it keeps the support of those voters who want the U.K. to leave the EU, so allowing the U.K. to stay in alignment with the EU or accepting the EU’s first offer would make them look weak,” he said. “The U.K. is not insisting on diverging from EU rules,” said David Paton, professor of industrial economics at Nottingham University Business School.

“Rather it is insisting that it will decide U.K. law. This might include deviation from EU rules at some point. That is perfectly normal for an independent country -- it would be most unusual for a country like the U.K. to agree to be bound by the laws of a foreign power or for any agreements to be decided by a foreign court such as the ECJ [European Court of Justice].”

“Brexit was meant to give the U.K. the freedom to adopt the standards that it chooses,” said Dr. Aris Georgopoulos, assistant professor in European and public law at the University of Nottingham.

“It will have to decide within the next few months whether it wants unrestricted access to the internal market and compromise on rule divergence or stick to the latter and jeopardize access to the internal market and face the economic consequences.”

Oliver Patel, Institute Manager and Research Associate at the UCL European Institute, said: “It increases the chances of no-deal. If the U.K. insists on divergence, thereby rejecting the EU's level playing field provisions, the chances of a deal are reduced. And if there is a deal without strong level playing field provisions, it stands less of a chance of being ratified.”

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has also ruled out extending talks beyond the end of 2020 and said if insufficient progress has been made, he is willing to walk away from talks as early as June to “decide whether the U.K.’s attention should move away from negotiations and focus solely on continuing domestic preparations to exit the transition period in an orderly fashion.”

In other words, a no-deal Brexit. This would mean the U.K. and EU would trade on WTO terms, which involves tariffs and trade barriers.

“It does seem as if the EU have not quite understood the new political reality in the U.K.,” Paton said.

“Whereas [former Prime Minister] Theresa May was fairly clear that she would not walk away without a deal, that is no longer the case with the new government. I think some people in the EU have, perhaps understandably, not quite grasped how serious the U.K. now is to leave the EU’s regulatory orbit.

“While the U.K. government keeps threatening a ‘no-deal’ scenario as a way to scare the EU into giving it what it wants, the reality is that this will hurt the U.K. much more than the EU,” Stafford said. “The EU are prepared to ‘take the hit’ of a ‘no-deal’ scenario if it keeps the EU intact.”

Level playing field

The EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier has said the EU would not accept a deal “at any price”. “It is crunch time for the 'unicorn' (unrealistic) Brexit that the Leave campaign promised in 2016,” said Georgopoulos. “Reality bites, and the (British) government will have to choose how much it can afford to shift its position.” The EU wants the trade agreement to use its regulations as a “reference point” in areas such as state aid, competition, employment and environmental standards, as well as other regulatory areas.

This would ensure a “level playing field for open and fair competition, given the EU and the U.K.’s geographic proximity and economic interdependence,” according to the EU’s negotiating mandate.

The EU wants to keep the U.K. in regulatory alignment, with a role for the ECJ and the option of imposing tariffs if London strays too far off the EU path.

But Johnson vehemently disagrees with this position, saying in a speech: “There is no need for a free trade agreement to involve accepting EU rules on competition policy, subsidies, social protection, the environment, or anything similar any more than the EU should be obliged to accept U.K. rules.”

“The EU has respected the autonomy of other major economies around the world such as Canada and Japan when signing trade deals with them. We just want the same,” a government spokesman said, adding the EU offered the U.S. zero tariffs without the level playing field commitments or legal oversight they asked of the U.K.

“The U.K.'s primary objective in the negotiations is to ensure that we restore our economic and political independence on 1 January 2021,” a British government spokesman said.

Barnier has doubled-down, however, telling reporters that the EU wanted “a level playing field with a country that has a very particular proximity -- a unique territorial and economic closeness, which is why it can’t be compared to Canada or South Korea or Japan.”

“‘Level playing field’ is an EU construct, not a piece of terminology which we use,” Johnson’s official spokesman said.

“The U.K. seems to want a very different kind of deal than the EU is prepared to give,” Stafford said.

“Initially, Barnier seemed open to the idea of a Canada-style agreement but seems to have cooled on the idea more recently, perhaps believing it to be unrealistic. If the EU gave the U.K. exactly what it wants, it would threaten the integrity of the single market and the EU itself. This is something EU leaders are not prepared to do.”

“Trade deals usually incorporate some agreements on standards, regulations, etc.,” Paton said.

“The U.K. would prefer a system of mutual recognition. The EU would like their rules to be a ‘reference point.’ A negotiated outcome somewhere between those two points is quite possible, as long as the EU does not insist on ECJ oversight.”

Future

“In trade negotiations, size matters. The EU clearly has the upper hand,” Georgopoulos said. The U.K.’s leverage lies in London, a European and indeed global financial hub, but even here, the EU is not at a total disadvantage, he argued. “Since the referendum, some trillions of euros of assets have moved from the City to the European Union as a precaution. There are also cities in the EU such as Dublin, Frankfurt and Paris that can benefit,” Georgopoulos said. “The upper hand remains with the EU, but not as much as before. After all, the U.K. is still more economically dependent on trade with the EU than vice versa, but Johnson's large majority gives him the credibility to make demands,” Patel said. “Given that the EU wants a deal, this puts the U.K. in a stronger position than it was for the previous negotiations.”

He continued: “It is certainly possible that the talks will be completed by 31 Dec., but there is only scope for a limited agreement with such a short time frame. As the government has outlawed extending the transition period, it is unlikely that there will be a comprehensive and far-reaching trade agreement.”

“The talks will more than likely be over by 31st December, although it isn’t clear if a deal will have been agreed by this point. Reaching a deal will not be easy, and there is a significant risk that the two sides will not be able to reach an agreement in the short time left,” Stafford said. “They (the ruling Conservative Party) will allow a ‘no-deal’ scenario if it keeps the party’s support base together.

“Whether there is a deep agreement will really depend on the EU,” Paton said. “Once it is clear that the U.K. is not going to agree to dynamic alignment, they will have to decide whether the economic benefits of continued tariff/quota-free trade outweigh the possibly political costs to EU centralization if the U.K. makes a success of life outside EU regulations.”

“The U.K. government are likely to do whatever keeps them in power, which at the moment seems to mean acting tough and not ‘giving in’ to the EU,” Stafford said.

“In the U.K., the EU is being portrayed as an unrelenting adversary, so if a deal isn’t achieved, it will be the EU’s fault, not the government. Conversely, if the government does get a deal, it will appear all the more impressive, given the portrayal of the EU.”

After Nesil Caliskan a by-election will be held in Jubilee ward in Enfield

After Nesil Caliskan a by-election will be held in Jubilee ward in Enfield Publishing the analysis, Labour’s Cllr Ergin Erbil said Everybody in Enfield deserves basic rights

Publishing the analysis, Labour’s Cllr Ergin Erbil said Everybody in Enfield deserves basic rights Gaza-Israel conflict Statement from Cllr Ergin Erbil, Leader of Enfield Council

Gaza-Israel conflict Statement from Cllr Ergin Erbil, Leader of Enfield Council Cllr Ergin Erbil was elected as the new Leader of Enfield Council

Cllr Ergin Erbil was elected as the new Leader of Enfield Council The European Union called on Turkey to uphold democratic values

The European Union called on Turkey to uphold democratic values Turkish citizens in London said Rights, Law, Justice

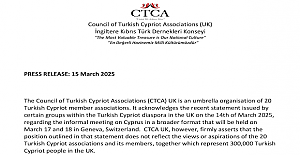

Turkish citizens in London said Rights, Law, Justice The Council of Turkish Cypriot Associations Geneva response letter

The Council of Turkish Cypriot Associations Geneva response letter Sustainable Development and ESG, Will This Become the Course for Turkic World

Sustainable Development and ESG, Will This Become the Course for Turkic World Saran Media And Euroleague Basketball Extend Media Rights Partnership for Four More Years

Saran Media And Euroleague Basketball Extend Media Rights Partnership for Four More Years Will Rangers be Jose Mourinho’s next victim?

Will Rangers be Jose Mourinho’s next victim? Jose Mourinho's Fenerbahce face Rangers on Thursday

Jose Mourinho's Fenerbahce face Rangers on Thursday Inzaghi stated that they felt the absence of our national player Hakan Çalhanoğlu

Inzaghi stated that they felt the absence of our national player Hakan Çalhanoğlu Trial used smart Wi-Fi sensors for live building occupancy data to optimise

Trial used smart Wi-Fi sensors for live building occupancy data to optimise Enfield Council at a special awards ceremony

Enfield Council at a special awards ceremony Enfield Council continues to invest in Edmonton, supported by £11.9 million in funding

Enfield Council continues to invest in Edmonton, supported by £11.9 million in funding Survey shows improvements in Enfield Council’s housing services

Survey shows improvements in Enfield Council’s housing services