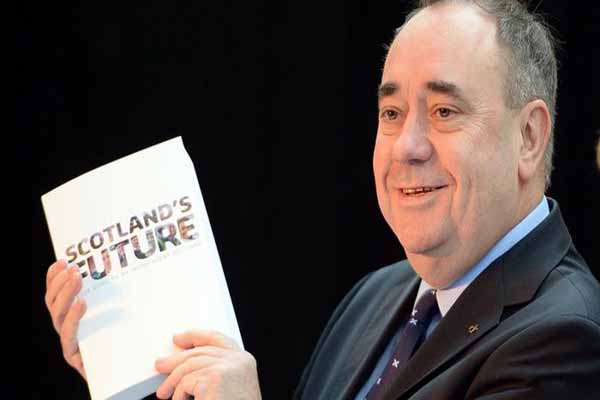

At the Bloomberg Future of Energy Summit in New York, Scotland's First Minister Alex Salmond, the man leading the charge for Scotland's independence in a September referendum was keen to sell his country on its strengths. "We have just over 8 percent of the UK's population and 1 percent of the EU's population," said Salmond. "But we have 90 percent of the UK's hydro capacity, 64 percent of the EU's oil reserves, 25 percent of the EU's offshore wind and tidal power potential, and 10 percent of its wave power potential. And we are 100 percent committed." But is Scotland committed to providing the education for the skilled workforce it will need to capitalize on this potential? Specifically: will an independent Scotland have the scientists and engineers to do the job?"Career pathway projections point to a shortage of trained individuals, which would leave a gap at all levels from technician to graduate," says Skills Development Scotland. The Scottish Funding Council (SFC) has increased university level funding for science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) subjects."We are also seeing a focus of research and postgraduate study around science and industry challenges through Innovation Centers, which offer new and exciting opportunities for collaboration between Scotland's academic and business base," says Alastair Sim, director of Universities Scotland, the representative body of Scotland's 19 higher education institutions. But the most recent report on Scotland's A-Level (final year of secondary education) math and science results would suggest they have their work cut out for them.

Scotland has plenty of natural resources - but does it have the scientists and engineers to back it up?

Enrolment in science subjects between 2007 and 2010 more than doubled. And the average grades achieved for math and science at A-level rose more or less consistently between 1996 and 2010. However, Scottish students are underperforming internationally. Results from the 2012 PISA test (Program for International Student Assessment) ranked the UK - and thereby Scotland - 26th for math and 21st for science. It is the first time the UK has not been in the top 20 for either subject area.

Jobs that don't yet exist

Some authorities on education argue that the PISA rankings only cover specific skills and that they overlook the concept of deeper learning and creativity - concepts that underpin Scotland's relatively new curriculum, the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE). The CfE offers an interdisciplinary and experienced-based approach to learning for primary through secondary schooling. Rather than adhering to a national curriculum, schools are encouraged to devise "active learning" modules that can encompass various subject areas, using people and places in their local communities.

The CfE's briefing on science education reads: "We need to prepare learners for jobs that don't exist, using technology that hasn't been invented to solve problems we can't yet imagine." "I really like the interdisciplinary principle, the way all the subjects are linked by a common theme," says Dr Simon Gage, director of the Edinburgh International Science Festival, which runs until April 20. "And I particularly like that creativity plays a central role in the curriculum," says Gage. "But the fact remains that science education funding at school level is extraordinarily low. You can't get hands on if you can't afford things to put your hands on!" So, just as the CfE hopes to inspire resourcefulness and creativity in students, its successful implementation also rests largely on the resourcefulness and creativity of school administrators. But Gage says the curriculum has proven difficult for some teachers.

"I think the CfE looks good on paper, but there hasn't been much in the way of support for teachers. I think it might take a number of years to bed down good working practices." A STEM to deeper learning The central question now is how Scotland should go about nurturing students so that they later contribute to the country's scientific workforce. "We need to better articulate career opportunities," says Gage. "We need to communicate to students that going on to university to do a science degree is like getting an armored passport - it can take you anywhere."

This is where STEM Scotland comes in. STEM Scotland is supported by the Office of the Chief Scientific Advisor of the Scottish Government, with the aim of championing science engagement in Scotland. The organization provides schools with STEM ambassadors: volunteers with workplace experience in STEM areas, who can encourage young people to pursue careers in science. Cassandra Lowson is the director of STEM Scotland for Scotland East. She says the job isn't always easy - but it's getting ever more pressing as the vote on independence draws nearer. "Our current struggle is finding suitable ambassadors in math. There are plenty of people out there with math qualifications but that doesn't mean they're working in the same field." And, as ever, money is a big problem. With the independence referendum looming, Lowson says she is "very concerned about [the future], with no contingency for funding beyond 2015." DW.DE

Prime Minister Keir Starmer's 2025 Easter message

Prime Minister Keir Starmer's 2025 Easter message After Nesil Caliskan a by-election will be held in Jubilee ward in Enfield

After Nesil Caliskan a by-election will be held in Jubilee ward in Enfield Publishing the analysis, Labour’s Cllr Ergin Erbil said Everybody in Enfield deserves basic rights

Publishing the analysis, Labour’s Cllr Ergin Erbil said Everybody in Enfield deserves basic rights Gaza-Israel conflict Statement from Cllr Ergin Erbil, Leader of Enfield Council

Gaza-Israel conflict Statement from Cllr Ergin Erbil, Leader of Enfield Council The European Union called on Turkey to uphold democratic values

The European Union called on Turkey to uphold democratic values Turkish citizens in London said Rights, Law, Justice

Turkish citizens in London said Rights, Law, Justice The Council of Turkish Cypriot Associations Geneva response letter

The Council of Turkish Cypriot Associations Geneva response letter Sustainable Development and ESG, Will This Become the Course for Turkic World

Sustainable Development and ESG, Will This Become the Course for Turkic World The 'Prince of Paris' has impressed in his first EuroLeague season

The 'Prince of Paris' has impressed in his first EuroLeague season Saran Media And Euroleague Basketball Extend Media Rights Partnership for Four More Years

Saran Media And Euroleague Basketball Extend Media Rights Partnership for Four More Years Will Rangers be Jose Mourinho’s next victim?

Will Rangers be Jose Mourinho’s next victim? Jose Mourinho's Fenerbahce face Rangers on Thursday

Jose Mourinho's Fenerbahce face Rangers on Thursday Barclays has become the biggest UK lender so far to cut mortgage rates

Barclays has become the biggest UK lender so far to cut mortgage rates THE SPRING STATEMENT EXPLAINED, UK ECONOMIC OUTLOOK AND GROWTH FORECASTS

THE SPRING STATEMENT EXPLAINED, UK ECONOMIC OUTLOOK AND GROWTH FORECASTS Launch of Made in Enfield gift shop to celebrate local artists and designers

Launch of Made in Enfield gift shop to celebrate local artists and designers Trial used smart Wi-Fi sensors for live building occupancy data to optimise

Trial used smart Wi-Fi sensors for live building occupancy data to optimise